|

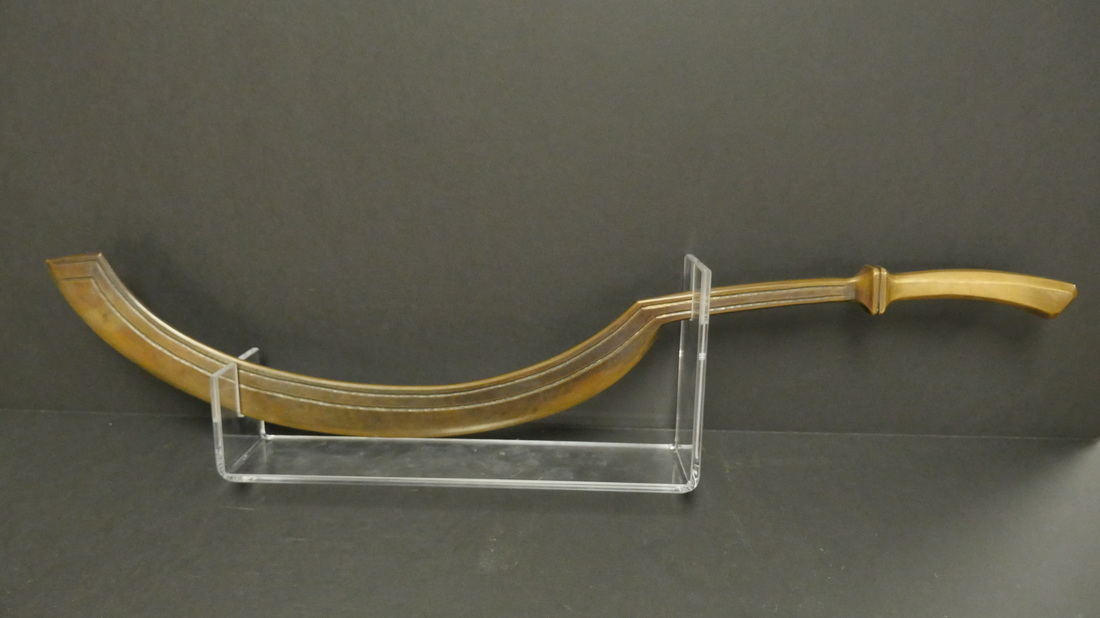

| Scimitar of Captain Edward Crofton (active 1804-1812) |

Evolved from a number of blade types across Asia over the early centuries of the first millennium, the initial swords of what could be historically grouped into scimitar family of blades were arguably forged between 600 and 700 BCE in central Turkey, but as form usually follows function with blades, the concept, and need for a curved blade is shown developing at multiple locations across the Asian continent, and later moving into southwestern europe and northern Africa.

By the time scimitar is first document as an English word in the 17th century, it had actually derived from the french word cimeterre, and that was derived from an Italian word scimitarra, who's linguistic heritage is entirely lost to history at this point. Generally speaking, the word by then was used to describe any curved blade of Asian, or north African origin.

The distinction was not small, either technically or culturally. Europe's heritage of straight, double edged swords with impressive size, and devastating striking power was well established by the time of the renaissance, and the majority of European engagements from Asia, be they military, or economic, has put the Asian preference for curved, fast, single edged weapons on full display for merchants, soldiers, and diplomats.

Much like the striking contrast and powerful social and political implications that the American M-16 and the Soviet AK-47 embodied during the cold war of the 70a and 80s,

the names 'sword' and "scimitar" likewise framed Europe's relationship with both its trading partners (silk road) and adversaries (Turkey, the Mongols, the Moors, the Persians).

In broad terms, the "Scimitar" could describe a number of different swords, with different methods of construction, different lengths, and different weights. However, the weapons did share some striking commonalities, almost all born of the function they were asked to serve.

|

| Two Scimitar family swords: an Egyptian sword in the shamshir style, and an Ottoman kilij |

First, the blades were undoubtedly light, at least when compared with the same amount of reach in a European blade of a similar time period. By the middle of the 12th or 14th centuries, the fundamentals of steel manufacture, metal forging, shaping, and honing were thoroughly understood across the many different countries of Asia and north Africa, and especially Persia (modern Iran), and at a level at least equal to that of europe, if not superior to in some examples. This is not to say the swords were superior to European weapons (or inferior), that is a much more nuanced conversation, but as deigned, they were made to be strong, and light, between 8 and 18 ounces lighter than a comparable European double-edged blade. The reduced weight was meant to help with the speed of a strike, and ease of shot placement, allowing a swordsman to capitalize on the velocity of his weapon for cutting power, where a western blade would more rely on mass and physical power to do its damage.

|

| Persian scimitar (shamshir). |

Second, the scimitar generally understood to be single edged (with some exceptions). In contrast to the European preference for edges on the leading and trailing sides of the blade, the scimitar's deign was meant to cut only in one direction. As to how much this affected, or restricted striking options for the user is a mater of worthwhile discussion, but not something that could be done justice here. However, this characteristic pairs closely with the lighter construction of the weapon, as it didn't need the back edge, less metal was needed overall, and the weapon's spine could be built up for support of the cutting edge.

|

| An example a highly ornate Persian scimitar (shamshir). |

Third, the scimitar is curved. This, perhaps more than anything else, is most recognized by westerners. The overwhelming majority of blades in europe dating back to the roman gladiolus were strait, and even into the later middle ages, daggers, all the way to great-swords carried that line true, with relatively few exceptions. With the Scimitar, there of course was no single pattern for how much curve the weapons had, so some examples are very mild, and other are drastic, though all of them draw from the same heritage. The armies of Persia, Turkey, North Africa, and the Mongols all made extensive use of Calvary as part of their military forces, the Mongols the most drastic example of that trend. This, combined with a drastically different set of philosophies and resources with regards to body armor in combat meant that when a rider made contact with the enemy, he was much more likely to strike fabric and flesh than plate and chain. The curve of the blades helped to keep them from getting stuck in their targets, or recoiling from too much of an impact across too much of the blade. Rather, the edge would bite into the flesh, and help promote a carry-through into deeper tissue, or just through the target and out the other side. The same science would be implemented in European cavalry sabers in the 16th and 17th centuries, and while its easy to accuse the latter of copying the former, both came to prominence with the rise of horse cavalry and the decline or absence of metal body armor.

|

| Ottoman scimitar (kilij). |

The Scimitar style of weapons was found as far north as Mongolia, and as far south as the Indian sub continent. Some examples in China and Japan are arguably Scimitar in style, though the southwestern Asian powers of Persia and Turkey, and the north African Moors were some of the most prolific practitioners, and manufacturers of the blade style.

Blades that are today considered part of the scimitar family of sword styles include:

the Persian Shamshir (modern Iran)

The Turkish Kilij (modern Turkey and and examples in modern Egypt)

The Nimcha (Morocco and North Africa)

The Pulwar (Afghanistan)

The Indian Talwar (Indian Subcontinent)

The Indian Kirpaan (Punjab, North Western India)

And the previously mentioned Shotel (Horn of Africa, primarily Ethiopia and Eritrea)

The scimitar is still considered a cultural icon, being used in movies, books, and even national flags and heraldry to codify part of the culture of the people being depicted.

|

| Official cover for a Saudi Arabian passport. Note the cross scimitars beneath the palm tree at the top. |

|

| Morgan Freeman holds an absurdly large scimitar for a 10th century moor in 1991's "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves" |

From Morgan Freeman's rather fanciful display of a scimitar wielding moor in the 1991 Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, to the arms of Saudi Arabia, the curved sword perseveres today as an icon and point of cultural heritage for a great many people across nations from three continents.

#Swordsunday is intended as a fun and educational series of posts for the enjoyment of readers.

His Lordship Ivo Blackhawk

Kingdom of Ansteorra

"Long Live the King!"

Kingdom of Ansteorra

"Long Live the King!"